La Magia de México

As a university runaway, I wanted to escape reading about Mesoamerican plants and get straight to the source!

At the time, I was preparing a dissertation for my History and Italian degree titled The Reception of Mesoamerican Plants in Renaissance Italy. One of my favourite sources was a letter written by a butler to the Medici, in which he recounted the Medici’s apprehension when offered a tomato for the very first time.

The upper classes of Europe wanted to flaunt the wealth they had acquired from the New World, but at the centre of this boast lay a deep fear of the mystical Americas. In books such as Bernal Díaz’s The Conquest of New Spain, he described exotic practices of indigenous peoples—including human sacrifice and the use of what some would call “plant medicines” or hallucinogens.

For God-fearing Catholics, these practices were far outside the norms of European society and were often denounced as demonic. Moreover, given the challenge indigenous Mesoamerican cultures posed to European tradition, Europeans had every reason to be wary of these faraway exports.

Aristocrats wanted to appear as pioneers. Among Italian elites, there was a rush to paint New World plants—potatoes, corn, tomatoes—on murals. But actually consuming these plants, and risking one’s health or life, was another matter entirely. This is exactly what my source highlights, and I find it fascinating.

I digress. I was immersed in literature on this topic, and all I wanted was to be in the land itself.

I set off in search of the exoticism described in the botanical texts I had been studying.

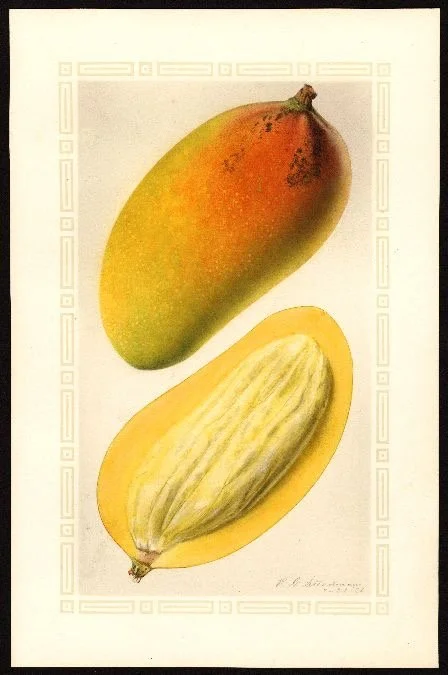

I arrived in what some call the ‘Mecca of Mexican Surf’, Puerto Escondido, and found my way to a beautiful home. At first, the fruits at local markets seemed exotic enough: papaya, dragon fruit, mangoes in every shape and size, chayote, jicama, and chilis in varieties I had never imagined.

Then I discovered the real treasure: my garden. Coconuts, of course, were familiar, but the gems were the chico sapote, the anona fruit—which my landlord and I hand-pollinated daily by transferring pollen from male to female flowers—guaya, and rambutan. I saw the moringa plant for the first time, climbed coconut trees to drink their water, and processed the meat to make coconut milk daily. I also ate my first jackfruit (yaca), which was enormous, and discovered carambola (starfruit). Absolutely scrumptious.

As I approach a more city-based life, I will treasure these memories and remain deeply grateful for the eight months I was fortunate to spend there.

What struck me most about Mexico is the profound respect people have for nature—as if it commands them. It is not a land for the faint-hearted, with mosquitoes carrying dengue and hurricane season serving as a reminder of our smallness in the face of nature’s power.

I hope to return one day—or at least take the lessons in gardening and living off the land and apply them wherever I go in the world